As artists, we seem to have this assumption that critique is a one-way street: we show a work to someone, without talking about the piece, and the person you’re showing it to gives their two cents about what works and what doesn’t.

The internet certainly hasn’t made this process easier: often, the artist doesn’t even write a good enough description of their piece to give context to the viewer.

If you want a great critique, you need two things:

Context, and Dialogue.

The two are interdependent. In a critique, you can’t have one without the other.

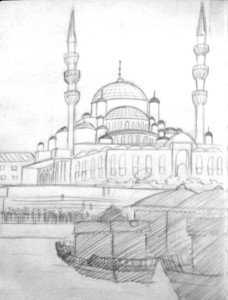

Let’s use a sketch I made as an example for what I’m talking about

If I were a novice, I would just show this and say, “What do you think?”

But that’s not the full story.

The full story behind the sketch is this:

“I’m trying to improve my ability to illustrate locations for a comic project I’m doing. I can’t draw the locales of the story yet, so I’m drawing from reference until I develop a wide enough visual vocabulary in my memory (and reference images folder) that I can create new places.

“This sketch was made for practice, to make sure I could still draw buildings and things.

“But I want it to pop visually. I want this picture to be uniquely Istanbul, but right now it’s flat and I don’t know how to make it pop. Colors, obviously, would help, but what colors? I know my lines aren’t straight (because I didn’t use a ruler to draw this), so I know the next time I draw a location, buildings, etc, I’m using a ruler.

“But what do you think I should do?”

So right there, I established context (why I drew this image) and dialogue (what do you think I should do next?).

If you are talking to someone who gives good critiques (like some professors, artistically-minded friends, etc), they now understand what you’re looking for and will critique appropriately.

Versus, if you didn’t give context for why you’re looking for critique, they will spot everything you already know (“You didn’t use a ruler” “It’s black and white” “Why is it still pencilled?”) and you will either

1) tune them out because they’re taking too long to get to the bits you want to hear, or

2) you’ll get discouraged and think, “Oh my god I’m a terrible artist! I suck!”

Or worst-case scenario, you will experience both 1) and 2).

The other thing you need to do when receiving critique is this:

Ask many people.

You can’t just ask one person for a critique and call it good. Make sure you ask as many people as you can for feedback. Don’t forget to add Context and Dialogue.

Write these notes down. That way you can reference and cross-reference later.

Then, sit down. Spot where everyone mentions the same thing. Does everyone seem to say you should use red? Or make the background hazy to distinguish perspective? Does one person say you should use blue for a building but another say purple?

Then (and this is most important): use the critiques that you found helpful and save the rest for later.

You shouldn’t throw away or ignore all the critiques that you don’t agree with (unless they’re haters. Haters gonna’ hate).

And it’s not that some critiques are irrelevant all the time. They’re just irrelevant for the moment. Keep them around for later so that next time you make art, you can use that critique as a jumping-off point.

In the comments below, let me know: when was the last time you got a critique? Do you think it was helpful or not? And more importantly, what did you do after?