Thanks for joining me in the first post of Writing for Comics 101. Today, you’ll learn that a comic is more than just cool-looking characters.

Here’s a common problem I see among aspiring comics creators: they create this cool character that hits all the right buttons for trendy clothes, kickass attitude, and more one-liners than Mystery Men.

But what do these folks do with their cool-looking characters?

Absolute fuck-all.

Here’s the thing – nobody cares about how cool your character looks. And nobody cares what kind of powers or cool abilities they have.

Readers do not care about the superficial crap. Readers care about the journey the character goes on.

If you want readers to be invested in your cool characters, you have to know how to develop that character to make them go on a story.

Here’s a super easy process to help you flesh out this character. I guarantee that by answering these questions, you’ll not only make actually believable characters. You’ll also actually find a plot that writes itself.

Here are the questions you need to ask about your cool character:

- What’s your character’s background?

- What do they want?

- What do they fear?

That’s it.

You may have seen quizzes and templates everywhere, from Tumblr to Pinterest. These character templates will ask questions like “what’s your character’s favorite food? What’s their fondest childhood memory?” etc etc.

That’s all superficial crap. Those can, and will, change during the writing and re-writing process.

But if you get the answer to those 3 questions up top? Your character will be SOLID.

Here, I’ll use one of my characters to illustrate this point.

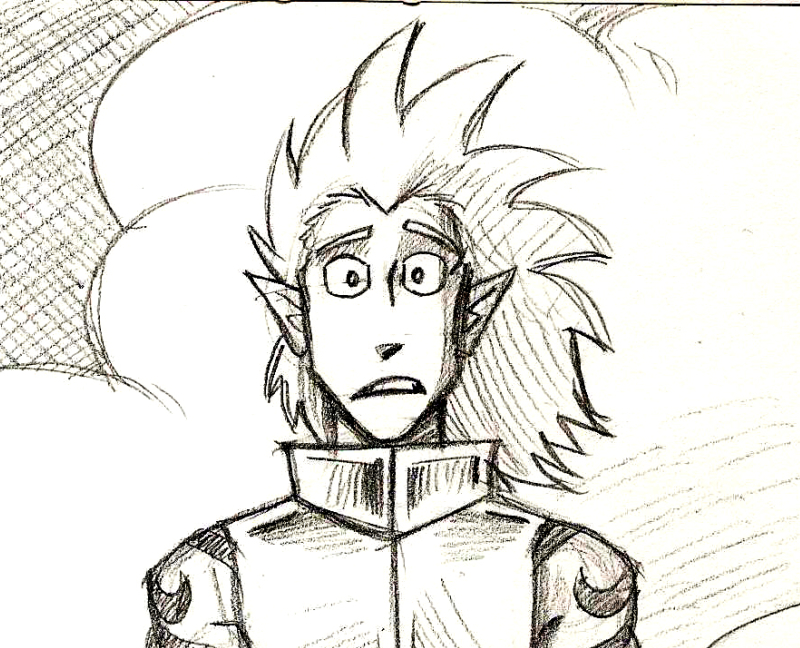

This is Auxaton.

What’s his background? He’s a mountain ridge elf, and a monk for the goddess Ahyahweh. His life is devoted to acts of community service, to help his people live in a cold environment.

What does he want? Well, recently ALL OF HIS PEOPLE have been kidnapped and enslaved. He wants to find his people so he can free them.

What does he fear? That he will lose his connection to his goddess.

And with that, we have a plot! A monk who has lost his people is on a journey to rescue them.

Now, folks who have studied film will say, “Wait, you didn’t address their need! Story is what a character wants vs what they need!”

You have already figured out their need – by asking what they fear.

What the character WANTS and what they NEED are two different things, but are usually tied together. For example, in the Disney movie Aladdin, Aladdin’s WANT is riches and a palace. He FEARS Jasmine discovering that he’s not a rich prince, but a beggar boy using magic to appear rich. His NEED is to stop pretending to be something that he isn’t.

So there you have it. Do this exercise and I guarantee that you will have yourself a character that’s worth exploring and writing about.

Stay tuned for more writing tips. And be sure to sign up for the email newsletter to know when the next Writing for Comics 101 drops.

That’s all for now. Thank you for reading!

You. Are. Awesome.